Note: This article is the sixth in an ongoing series on valuation and capitalization. To learn more about the financial mechanics of early stage investing, download this free eBook today Angel Investing by the Numbers: Valuation, Capitalization, Portfolio Construction and Startup Economics or purchase our books at Amazon.com.

Having evaluated four common methods for valuing early stage companies in a previous article, it's time to take a closer look at the Seraf Method which builds on everything great that has come before it (with the debt of gratitude acknowledged!), but adds key refinements necessary to make it work reliably in real life.

In a nutshell, the Seraf Method consists of four simple steps, which we have boiled down into three worksheets and a look-up table.

-

The first step is to consider the exit practicalities for the company (below),

-

The next step is to think about the financing requirements,

-

The third step is to look at the current fund-raising market conditions and current deal details and

-

The fourth and final step is to look up your valuation on the adjusted “curve” on the Valuation Look-Up Table.

To help you visualize the method overall, here is a diagram showing the forces at work:

The key underlying premise of the Seraf Method is that percentage ownership is the yardstick that allows you to compare a risk-adjusted valuation to market norms. I think it is important to point out that by using percentages we do not mean to imply that percentage ownership is a particular goal for angels. But rather it is that thinking of it in terms of percentage ownership provides a relative gauge for how a deal valuation stacks up. For venture capitalists, owning a precise percentage is important for reasons of time management and fund returns math (and sometimes, though not often, for control over decision-making - usually that is achieved contractually).

But for angels, this focus on percentage ownership does not really apply to the same extent for several reasons:

-

The percentage ownership we are talking about here is ownership by the entire class of investors (e.g. all Series Seed or all Series A investors as a class) and it is split amongst a large group of individuals who will each own a slice of it.

-

Angels tend to go into companies at such an early stage that they must make a larger number of lower conviction bets than VCs who are often deploying their biggest chunks of money when companies are more established and starting to go into expansion mode.

-

Angels are not hired portfolio managers who need to sit on the board of every investment they make - someone needs to sit on each board, but an angel might only be the board delegate to 1 out of every 10 or 15 of their deals.

So while the Seraf Method revolves around the concept of percentage ownership, it is just a means, not an end. We use percentage ownership because historical market norms allow us to use percentage ownership as a guideline or yardstick (see our discussion on utilizing the Valuation Look-Up Table).

To use the Seraf Method is pretty simple. Assuming you have done some basic diligence on the company and have a sense of its intended path, you simply buzz through each of the first three worksheets, and the spreadsheet sums up the results and applies that correction to the “curve” embodied in the Valuation Look-Up Table. So without further adieu, let’s look at the worksheets.

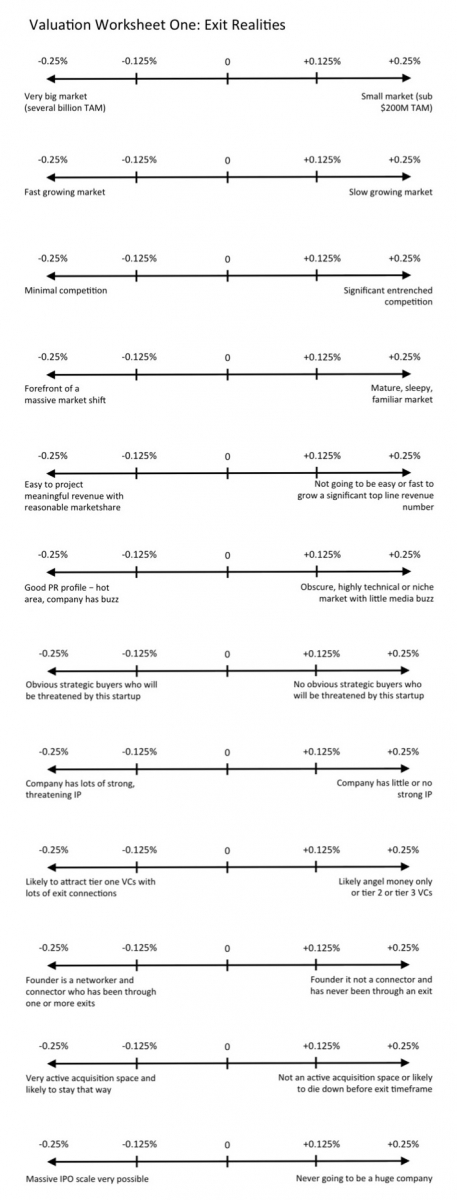

Seraf Method Worksheet One: Exit Practicalities

The purpose of Worksheet One is to ballpark the kind of exit that might be possible and use that to create the first set of adjustments to the starting valuation. But to drive home the importance of doing this exit analysis, we first need to set some context about startup exits as a background for using Worksheet One.

As we have noted in previous posts on Raising the Right Amount of Financing to Achieve a Successful Exit and Financials & Funding Strategy, investors can make money in any type of exit, provided the company is capitalized appropriately for that exit. You cannot pour $10M into a company and sell it for $15M and expect to make a good return. In that scenario, even if investors owned 66% of the company, they would still be looking at a 1X. So in thinking about the valuation for a company (and the capital staging plan), you have to start with the realities of what kind of exit the company could reasonably expect to achieve.

For most companies, an IPO is not a realistic possibility. For a lot of reasons (which are beyond the scope of this discussion), the market for all but the most marquee IPOs is very weak. As a result, only a very tiny fraction of startups will live to see an IPO - the number is way less than 1%. Here’s the math behind that: conventional wisdom holds that 90% of startups have failed before they reach 5 years old. Even if we conservatively knock that down to a 75% failure rate, of the 25% that do survive, a recent CB Insights Report found that 97% of startups are acquired and 3% did an IPO. So 3% of 25% is 0.75%. And those numbers appear to be going down over a long trend line. In 1997 there were over 7,000 public companies in the US. Now there are less than 4,000. Conclusion: most startups should plan on an exit by M&A.

So how about the deals that do get done? As we previously outlined in detail in our discussion of exit strategy, most exit scenarios can be categorized into one of the following five buckets, whereby the acquirer will either:

-

Buy the Team - Company has limited if any intrinsic value beyond the knowledge and experience of the team. Acquirer’s objective is to hire the people (i.e Acqui-Hire).

-

Buy the Technology - Company has some Intellectual Property (IP) in addition to the knowledge and experience of the team. Acquirer’s objective is to hire the people and obtain control of the IP.

-

Buy the Feature - Company’s technology has some proven capability, but has achieved limited market acceptance. Acquirer is adding a “feature” to its existing product line along with the people who created the IP.

-

Buy the Product - Company has built a product with early market acceptance and they are nearing product/market fit. Acquirer is buying a product with some traction that they can apply significant sales and marketing resources to and increase growth.

-

Buy the Business - Company has built a viable, profitable stand-alone business that is centered around one product or a series of closely-related products. Acquirer views this as the purchase of a growth business with the intent of accelerating the growth and increasing profitability.

Most M&A deals are smaller than you might think. Those last two categories (buy the product, or buy the business) are what you are shooting for. If you look at the exit practicalities and you cannot foresee circumstances that could drive it into one of those categories, you are not likely to get a great exit valuation, nor a great return, and you should pay a lower valuation upon your initial investment in the company.

Even if you can find a buyer who will pay a good revenue or EBITDA multiple, you still need meaningful revenue or EBITDA with which to multiply. And before you make huge assumptions on what kind of revenue might be possible, you should sanity check what kind of market share that number would represent. It is unusual to see a small company enter an established market and gobble up 75%+ market share unless they created the market themselves. (Yes, I know Google did it - it does happen - but I stand by my assertion that it is very rare and associated with massive shifts in technologies and markets).

Assuming you can project decent revenue and margins, a good way to get a sense of whether buyers might be interested, is to look at it through a strategic lens. As we discuss in detail in our article on exit strategy, there are numerous scenarios where a large company makes an acquisition, but the following 5 cases are the ones that create the most motivation for acquirers and the most value for the investor:

-

A new product that complements a fast growing product line of a large company

-

A disruptive product that has the potential to damage a larger company’s market position or become difficult to “sell around”

-

A new product that fills a newly emerging gap in a big company’s product line

-

A new product with strategic patents that a buyer cannot risk having fall into a competitor’s hands

-

A new product that is clearly constrained by lack of sales and would be instantly accretive and profitable in the hands of a larger sales force or sold to an existing customer base.

This list is not exhaustive, but it does cover the outcomes that will produce some of the greatest returns to investors. You will notice that of the original five buckets, the acquisitions of teams, technology and features are not reflected in any of these high value scenarios. So-called “acqui-hires” are a particular issue: they might produce a good financial return for the company founders (especially if the buyer creates a “carve-out” from the proceeds to be paid directly to the team as an inducement for doing the deal) and therefore be attractive and tempting to the management team, but they rarely turn out to be great returns for the early stage investor.

Other exit factors will include issues like intellectual property that could pose a major threat to a big company, the experience and transferability of the team, market characteristics, competition, timing, other investors, and the current events situation around the company.

The goal of Worksheet One is to walk you through a series of simple questions to help you make “Exit Realities” adjustments to your valuation. When you boil all the relevant concepts down, here is how it looks (access a downloadable version here). For each topic you want to “set the slider” in the right place and tally up your resulting Worksheet One sub-total to be carried forward:

Now that we've looked at the first part of the Seraf Method, Exit Practicalities, let's take a closer look at Worksheet Two: Financing Requirements.

Want to learn more about the financial mechanics of early stage investing? Download this free eBook today Angel Investing by the Numbers: Valuation, Capitalization, Portfolio Construction and Startup Economics or purchase our books at Amazon.com.