Note: This article is the fifth in an ongoing series on valuation and capitalization. To learn more about the financial mechanics of early stage investing, download this free eBook today Angel Investing by the Numbers: Valuation, Capitalization, Portfolio Construction and Startup Economics or purchase our books at Amazon.com.

In Part I of this article we addressed why setting a fair valuation on a startup company is so hard and treated with such great importance by both the investor and the entrepreneur, along with what kinds of constraints are placed on these valuation discussions. Now let's take a look at four of the most common methods for valuing early stage companies.

In Part I of this article we addressed why setting a fair valuation on a startup company is so hard and treated with such great importance by both the investor and the entrepreneur, along with what kinds of constraints are placed on these valuation discussions. Now let's take a look at four of the most common methods for valuing early stage companies.

OK, so finding the right valuation is really hard, somewhat arbitrary and yet really important. How do investors do it? What are some of the most common approaches you’ve seen applied to valuing early stage companies?

It is anyone’s guess how valuations have historically been derived in the most informal parts of the angel investing world, where one-off founders and one-off investors just try to get a business launched. I suspect people approximate and try to see what feels fair and reasonable and let the chips fall where they may (probably learning hard lessons in the process). But in the more organized angel investing world, where investors do a lot of deals that are focused on high-growth, high-potential startups, there are four slightly more formal methods that have been predominate. Each method is quite straightforward and easy to explain to both investors and entrepreneurs. But, each method has drawbacks. I will explain those in a moment, in addition to suggesting a better approach. But let me summarize these four methods first.

Four Traditional Methods For Valuing Start-Ups

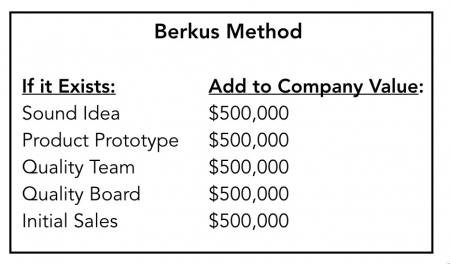

The first three out of the four start with the notion of adding and subtracting value based on a variety of factors. Let’s start with what is commonly referred to as the Berkus Method, named after my friend and colleague and well-known angel investor Dave Berkus. In the Berkus Method (acknowledged by Dave Berkus as needing updating), you basically look at five aspects of the company and assign some value to each one:

As you can see, this method accounts for some of the main risk factors and attempts to give an admittedly arbitrary value in exchange for ticking the boxes on each one. A user of this model can refine it by changing the amount added across the board to reflect higher or lower prevailing average market valuations (i.e. have the factors add up to something different than $2.5M), but overall it is a relatively easy, rugged and somewhat over-simplified model.

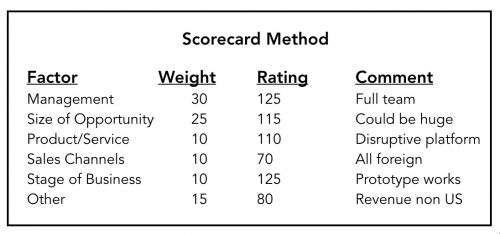

In recognition of the limitations of the Berkus Method, my friend and colleague and well-known angel investor Bill Payne set out to improve on it with what he called the “Scorecard Method.” Bill essentially asked “What if we look at more factors, give each one a relative weighting to reflect its importance, and a rating to score how well the company does on that factor?” So, for example a company might get a minor ding in valuation for scoring poorly on an unimportant factor, and a bigger ding for scoring poorly on an important one:

The Payne Scorecard Method then goes to pick an arbitrary starting point or “pre-money multiplier” of, for example, $2.25M, then takes the weighted average of the factors and multiplies it against the pre-money multiplier. So in the example above, the weighted average rating works out to 1.0875, which you then multiply by the pre-money multiplier to come up with a pre-money of $2,446,875 (or 1.0875 x $2.25M).

As you can see from above, this method brings a few more factors into play, and allows you to fine tune it with both weighting and scores, but it still leaves a lot of key issues out and relies on a tremendous amount of subjectivity. Plus, you still have to pick an arbitrary pre-money multiplier in the first place!

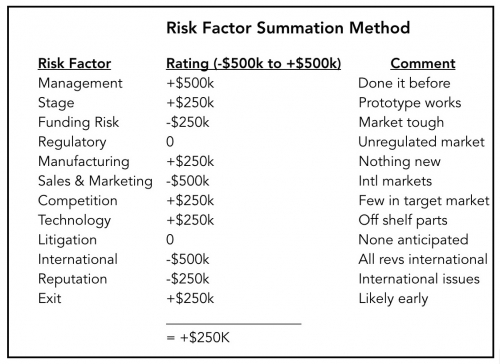

The third method is yet another incremental improvement on the Berkus and Payne approaches - it takes concepts from both and combines them. This method is called the Risk Factor Summation Method and simply takes a similar pre-money starting point, adds a longer list of factors and allows you to score each factor on a scale of +$500K to -$500K. So using the same example:

Once you net out the rating column at +$250K, you add that to the pre-money starting point of $2.25M and come up with a pre-money valuation of $2.5M.

Again, the Risk Factor Summation Method is an improvement in both sophistication and granularity, but still feels a bit arbitrary given that you have to pick a starting point and decide how much to add to each factor.

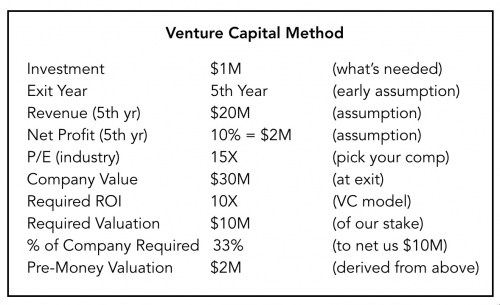

The fourth method is one angels have borrowed from the VC industry and so it is typically referred to as the Venture Capital Method. As Bill Payne explains it, the Venture Capital Method is all about projecting a future state and then working backwards from there to derive your required valuation.

Here’s an example: let’s say a company needs $1M, and we assume it will exit by M&A in year 5. Let’s further assume it will have revenue of $20M that fifth year (optimistic, but certainly possible.) And we will assume it will have net profit of 10% or $2M which will yield it a somewhat economically standard price/earnings ratio of 15X.

That means that the company would be worth $30M on exit (15 P/E ratio x $2M in earnings). If investors require a cash-on-cash return of 10 times their money, then the value of their stake in the company must be $10M at exit ($1M investment x 10). If they need $10M out of a $30M exit, that is one third, so they need to own 33% of the company. Therefore, if they are putting in $1M, and need to own a third, then the pre-money must be set at $2M. Here it is in table format:

As you can see from this fourth method, it brings some real world context into things. But it is still pretty simplistic because it only assumes one round of financing and would get pretty complicated as you try to make it track actual reality.

So these four common methods have their limitations. When you are negotiating valuations with an entrepreneur, do you use any of these methods, or do you take a different approach?

I know what you are thinking. There has to be a better way. And we think there is. We really don’t use these approaches much, favoring our own path which we have developed over time. Our approach continues the tradition of building on everything great that has come before it (with the debt of gratitude acknowledged!), but adds key refinements necessary to make it work reliably in real life. For lack of a better term, let’s call it the Seraf Method.

In a nutshell, the Seraf Method consists of four simple steps, which we have boiled down into three worksheets and a lookup table. Read the next article in this series for guidelines on using the Seraf Method to value early stage companies.

Want to learn more about the financial mechanics of early stage investing? Download this free eBook today Angel Investing by the Numbers: Valuation, Capitalization, Portfolio Construction and Startup Economics or purchase our books at Amazon.com.