Note: This article is the fourth in an ongoing series on Early-Stage Deal Terms. To learn more about navigating term sheets and investment documents, download this free eBook today Understanding Early-Stage Deal Terms or purchase our books at Amazon.com.

In a previous article, we observed that the concepts covered in a typical term sheet can be grouped into four main categories of investor concerns: Deal Economics; Investor Rights/Protection; Governance, Management & Control; and Exits/Liquidity. In the next article we gave an overview and mapping of all of the key term sheet clauses used by investors to address the concerns in each category. In each of the next four installments, we are going to dig deeper into the concepts and nuances involved in the provisions belonging to each category. First up are the provisions relating to Deal Economics.

Round Size

One of the first questions to be tackled is the size of the round (i.e. how much money will be invested.) Here pragmatism rules the day. Since the company’s valuation is only going to go up with time and accomplishments, you always want to raise as little money as possible at today’s valuation. However, there are three countervailing factors arguing in favor of doing a bigger round:

-

It takes time and capital to accomplish milestones that matter,

-

The future funding climate is always less certain than the present funding climate, and

-

Each fund-raising event costs money and takes a great deal of founder time.

These factors amount to a solid argument for always raising a little bit more than a company thinks it absolutely needs. Things always take longer and cost more than management expects. So smart entrepreneurs and investors generally look at the key near term milestones the company needs to achieve, make a generous cost projection, and then add maybe 25% on top of that. In theory there might be a little extra dilution with this approach, but there are time and transactions savings. Nine times out of ten, the company needs the money anyway!

Valuation

Valuation is a long and therefore separate topic, but suffice it to say, it is one of the most critical aspects of any deal. It is usually set by the market (i.e. by the lead investor based on what she thinks it will take to fill the round), and that analysis is usually guided by a number of different modeling techniques and informed by experience and knowledge of her market.

Option Pool Size

New investors are often puzzled by the fact that the size of the option pool is a headline issue right up there with the size of the round and the price. Shouldn’t that operational detail be one of the last issues discussed? No, because the size of the option pool is closely linked to the valuation. For an in depth look at option economics see Pure Upside: Understanding Stock Options and Restricted Stock for Angels.

Example Termsheet Option Pool Language:

“The total number of pre-money shares to include an unallocated employee pool large enough on a pre-money basis to equal _[10-15]_% of the total fully diluted post-money capitalization, including founders’ shares, outstanding warrants and options.”

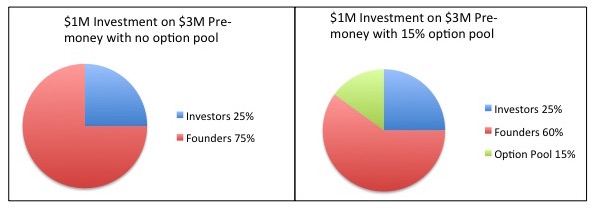

Investors always want the company to establish that pool prior to their investment so that the creation of the pool does not dilute their ownership and raise the effective valuation of the deal. Investors want to invest in a company which has the tools necessary to attract and retain talent (i.e. employee stock options). The bigger the pool, the bigger the tool, so investors want a good sized pool. However, since it is coming out of the pre-investment cap table, the dilutive effect for the founders is similar to a change in price. This simple chart shows a comparison of how post investment founder ownership changes with the creation of an option pool. They clearly own less of the company, but economically they are just as well off because the company has a critical tool for growth, so the dilution should be very well spent.

Liquidation Preference

The liquidation preference is a repayment priority associated with the shares on offer. Preferred stockholders are always entitled to repayment before common stockholders, but the liquidation preference provision specifies key details like:

-

whether they are entitled to more than 1X their original money before common stock shareholders get paid, or

-

whether they are entitled to participate with common stock shareholders after they have been paid back their original principal.

Preferred always has the right to convert to common stock, and if the per share price in the exit transaction is high enough, they will get a better return by converting than they will by just taking their original money back. But from time to time over the years liquidation preferences in excess of 1X have come briefly into fashion (e.g. the right to be paid 2X or 3X your original money before others are paid). That approach makes the clause into more of an offensive clause (getting a return) than a defensive clause (merely getting your principal back) and introduces financing dynamics that tend to destroy the company over time. This is especially true if they occur in an earlier round - all subsequent rounds want terms at least as good as earlier rounds, and so as the offensive liquidation preferences add up and the stack of money due to be paid out before founders mushrooms very quickly. If that stack gets big enough, founders have little prospect of earning a return. That can render the company unfundable because later investors don’t want to invest in a company where the founders aren’t going to work with all their heart because they have no reasonable expectation of return.

One compromise in the middle is called participating preferred stock. Holders of participating preferred reserve the right to get their initial principal back first, but then also convert into common and get their share of the pay-out as a common stockholder. The reason it is a middle ground is that it is neither offensive nor defensive. This approach doesn’t do much for them in a horrible outcome (where they will be lucky if there is enough to even pay some of their preference), and it doesn’t really change the economics much in a grand-slam home run scenario (where the vast majority of returns is a function of the value of the common). What it does is give the holder a modest proportional sliding-scale return in a mediocre outcome. And it does so without the obnoxious, glaring hard-coded non-linear return they’d get with a liquidation preference of greater than 1X.

The decision regarding when to take your preference and when to convert can be a tricky one, and it can be tricky to calculate the returns to common until you understand who will convert when. This cascading chain of action-consequence-reaction-consequence is sometimes referred to as a waterfall and a device called a waterfall diagram is sometimes used to graphically depict it. Going into great detail on waterfalls is beyond the scope of this piece, but for those who are interested, here is a sample cap table and waterfall analysis tool. In it you can see how as exit value rises beyond various thresholds, the value available for distribution to common increases (and the incentive to convert to common kicks in).

Example Termsheet Liquidation Preference Language (Non-Participating Preferred):

“One times the Original Purchase Price plus declared but unpaid dividends on each share of Series Seed, balance of proceeds paid to Common. A merger, reorganization or similar transaction will be treated as a liquidation.”

Example Termsheet Liquidation Preference Language (Participating Preferred):

“In the event of a sale, liquidation, dissolution or winding up of the Company, the proceeds shall be paid as follows: first, the original purchase price (i.e. 1X) plus declared and unpaid dividends shall be paid on each share of Series Seed Stock. Thereafter, the Series Seed Stock participates with the Common Stock on an as-converted basis.

A merger or consolidation (other than one in which stockholders of the Company own a majority by voting power of the outstanding shares of the surviving or acquiring corporation) and a sale, lease, transfer or other disposition of all or substantially all of the assets of the Company will be treated as a liquidation event, thereby triggering payment of the liquidation preferences described above unless the holders of a majority of the Series A Preferred elect otherwise.”

Dividends

It is very unusual for a high growth startup to pay regular cash dividends. The cash would theoretically generate a better return for shareholders if reinvested in growth and share price appreciation. But you do often see accruing dividends, which do not pay cash out in the present, but specify that they are to be paid at some future date, upon certain contingencies, or at the board’s discretion. These accruing dividends can specify payment in cash, common stock or preferred stock. Aside from delivering a slightly better overall return for stockholders, these dividends serve a very useful secondary function: they keep a time clock on the entrepreneurs to make sure there is some compensation to investors for the excessive passage of time. The more time has passed, or the earlier you became a stockholder, the more your dividends amount to.

Example Termsheet Dividends Language:

“Series Seed shall be entitled to non cumulative dividends as, when and if declared. Series Seed Stock to participate in all dividends declared on an “as converted” basis. No dividends payable on Common Stock or any other Class of Preferred without payment of similar and all accrued dividends to the Series Seed Stock.”

Next in this deal terms series, we’ll look at the clauses in the Investor Rights/Protection category.

To learn more about navigating term sheets and investment documents, download this free eBook today Understanding Early-Stage Deal Terms or purchase our books at Amazon.com.